Woosh! Bam! Honk!

Last year, the Ontario legislature decided to do something about traffic in Toronto. Subsidiarity? They know about as much about that as Strider about second breakfast. And they come up with a solution about as subtle and safe as a young Took’s actions when faced with a pile of rocks and murky places to throw them into. Congestion pricing is for schmucks in New York, London, or Singapore. In Ontario, the answer is to “rip out” some bike lanes. Hence the legislature, in its wisdom, required the Minister of Transportation to do just that.

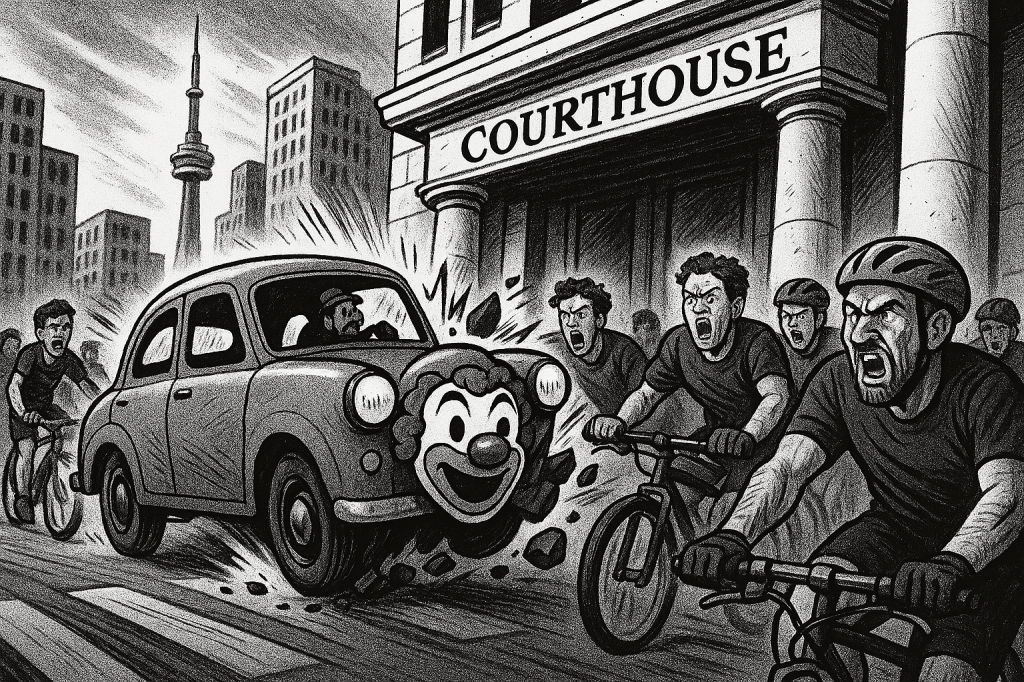

So the Minister threw his jackhammer into the trunk of his clown car and went off to do just that. Unfortunately for him, his path crossed that of a peloton of disgruntled cyclists and, in a clumsy attempt to swerve out of their path, crashed into the wall of a nearby courthouse. It looked a bit like this:

What I’m talking about is, of course, the Superior Court’s decision in Cycle Toronto v Ontario (Attorney General), 2025 ONSC 4397. Justice Schabas holds “that removal of the target bike lanes will put people at increased risk of harm and death which engages the right to life and security of the person” [12] and, further, that this “is arbitrary and grossly disproportionate, and therefore not in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice”. [13] This has resulted in more clown cars arriving on the scene, loudly tooting their well-practiced horns to demand the invocation of the Charter‘s “notwithstanding clause” so that $50,000,000 of taxpayer money can be dumped into demolishing the bike lanes that $27,000,000 of it had previously been spent building. All in the name of common sense and democracy, naturally.

When I started writing this post, I thought that Justice Schabas must be wrong, though it was a closer call than many of his critics allowed. I have changed my mind. This won’t be a popular opinion, but I think that, while counterintuitive — including to me — his decision is correct, given the unusual circumstances of the case. But even if it were not, the demands for the notwithstanding clause to be used to deal with his judgment are as uncalled for as they are predictable.

The Empirical U-Turn

The reason Cycle Toronto has aroused such strong feelings is that, at first glance, its outcome looks like it’s creating a constitutional right to bike lanes. That seems absurd, and of course section 7 of the Charter does not obviously contemplate such a thing. It provides that “[e]veryone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice”. People with guns taking you to prison? Sure. People with shovels digging up Yonge St? Not so fast.

The government pressed this point on Justice Schabas. He insists there is nothing to it:

[T]he Applicants do not seek a declaration that they have a positive constitutional right to bike lanes on public roads. The Applicants do not request or seek a court order that the government take affirmative steps to build more bike lanes. Nor do they challenge the provision requiring provincial approval for new bike lanes that involve removing a lane of motor vehicle traffic, which remains in the law passed on June 5, 2025. [17]

But that might be a little too cute. What the applicants’ arguments accepted by Justice Schabas amount to is that, while they admittedly cannot force the government to build more bike lanes where none existed before, removing the ones the government had previously built is another matter. If not exactly a constitutional right to bike lanes, is it a constitutional ratchet?

Again, Justice Schabas is aware of the point and rejects it. He explains:

[G]overnments may take steps that may put people in harm’s way by removing something, but they can only do so if the actions are in furtherance of legitimate policy decisions as opposed to being arbitrary, overly broad, or grossly disproportionate to the government objectives. In [Barbra Schlifer Commemorative Clinic v. Canada (Attorney General), 2014 ONSC 5140, discussed here] there was evidence that the government had consulted widely and, based on “a wide array of social science, statistical and expert evidence”, had made a legitimate policy decision that could not be described as arbitrary or grossly disproportionate: at para. 79. That is not the case here. [153]

In other words: there is no constitutional ratchet, because the government can always remove benefits, repeal policies, and rip out bike lanes, even when — as here — people can show that this will expose them to increased danger of injury or death (thus triggering the protection of a right to life and to security of the person). The catch? The the removals, repeals, and rippings out cannot be arbitrary and must be at least somewhat proportionate to what they will achieve, thus complying with the requirements of fundamental justice articulated by the Supreme Court in a long series of cases.

I think this is a serious argument, though perhaps it could have been better put. The claim Justice Schabas accepts is not that the government is constitutionally responsible for preventing harms to people caused by the action of others, or indeed by natural forces and circumstances. It is, rather, that when the government does act — and especially when it acts on things, like streets and bike lanes, within its own exclusive control — it cannot do so regardless of the predictable consequences.

Now, Justice Schabas’s references to “legitimate policy decisions” and to consultation are unfortunate: neither is a criterion at the section 7 stage. The former might be a paraphrase of the “pressing and substantial objective” prong of the test for justified limitations of rights under section 1 of the Charter. The latter, for its part might be a reason for deference to the government’s assessment of the evidence. But it is ultimately that, and not consultation, which matter.

This brings me to the issue that is probably at the real heart of the case: how does a court decide whether a policy decision like the one to remove bike lanes is arbitrary and hence unconstitutional if it exposes people to additional danger? Part of what incenses Justice Schabas’s critics is that they think it is not the courts’ role to do that. Or at least, they would like the courts to be cautious and deferential if they must. This blog’s longtime readers may remember that I have, once upon a time, expressed ambivalent feelings about these issues, when I used to write about what what I referred to, following Kerri Froc’s lead, “the empirical turn in Charter litigation”.

Justice Schabas has thought about this too, at least up to a point. He insists that there is no need to worry about the courts taking over the government’s policymaking role. After all, “most traffic and road design decisions are not made arbitrarily nor do they increase the risk of harm”, [156] because they are guided by the application of expertise. There will never be a serious prospect of a successful challenge to them. The problem in Cycle Toronto is that some bike lanes were chosen for demolition based on vibes (my word, not Justice Schabas’s), rather on any serious assessment of that decision’s effect. Justice Schabas doesn’t say so, but I am tempted to add that there is a reason why decisions about how to design a particular road are not normally taken by provincial legislatures but by people with some combination of technical expertise and local knowledge.

But this might not be altogether reassuring, for a number of reasons. For some people, this very privileging of expertise-informed decisions over those driven by raw political will is a problem. I have no particular sympathy for this, let alone when lives are at stake — and there is no dispute at all that they are here. Indeed I find this position quite callous. But there are subtler concerns that deserve more consideration. Notably, courts aren’t necessarily well equipped to assess empirical evidence; this evidence is often somewhat speculative; and it may the product of a biased scientific or social scientific professional milieu. The government had put the bias concern to Justice Schabas, who rejects it. There are also broader systemic issues, such as the possibility that the importance of evidence in section 7 cases will privilege some types of cases or claimants over others, but that is not what the critics of Cycle Toronto have in mind.

To my mind, these issues are real, but they need not be insuperable. They are things to be aware of (as Justice Schabas is, in part, though he may be a bit too glib), but not reasons not to entertain Charter cases that turn on empirical evidence, or indeed on scientific prediction. One must keep in mind, of course, that the standard for establishing a violation of section 7 is not whether the court agrees that the government has struck the right balance between its policy objectives and the relevant risks. It is whether the government’s action is arbitrary, in the sense of not advancing its stated aims at all. This is an inherently deferential rule.

Did Justice Schabas misapply this test? It is worth pointing out that the advice the government itself received rior to introducing the legislation at issue — including from the Canadian automobile association! — “was that protected bike lanes can have a positive impact on congestion and that removing them would do little, if anything, to alleviate gridlock, and may worsen congestion”. [66] That was evidently disregarded, and the government acted on what might generously be called intuitions. The only evidence it introduced in litigation was a report that, seemingly, did not even try to distinguish the effects of bike lanes on traffic from those of “other reasons for congestion, such as lane closures for street patios, construction, the adoption of reduced speed limits, and adjustment of traffic signals at intersections”. [92]

To my mind, Justice Schabas is not wrong not to attach much weight to this. The arbitrariness standard may be deferential, but I don’t think it requires an uncritical acceptance of claims that are quite evidently not responsive to the key question. The government simply did not have evidence — however imperfect — that to support its view that “ripping out” three bike lanes chosen for no discernible reason would reduce congestion. It acted on a whim — arbitrarily — and Justice Schabas was entitled to say so.

Like Justice Schabas, I suspect this is a highly unusual case, and one need not fear its having systemic repercussions. Governments mostly act on at least some evidence and for some articulable reason, which was not the case here. But unusual does not mean unique. Remember the litigation that ended with Ontario (Attorney General) v Working Families Coalition (Canada) Inc, 2025 SCC 5? (I blogged about the Court of Appeal’s decision in that case here; one of these days I should write about the Supreme Court one.) That started when the Ontario government decided to bring the application of its pre-electoral political censorship regime forward from six months to a year before the start of an election campaign — for no reason at all. The Superior Court duly said that the extension, at any rate, was not “demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society”, which was fair enough since the government couldn’t be arsed to justify it at all. And their response to the ruling was to try to get the censorship extension into law anyway by using the notwithstanding clause. Unsurprisingly, the parts of the Twitterverse want more of the same now.

Not… Again!

I’ve had plenty to say about section 33 of the Charter over the years and won’t repeat it all. Yes, it’s part of the Charter, in the same way as the provisions governing disallowance of provincial legislation are part of the Constitution Act, 1867. These provisions being part of their respective Constitution Acts does not justify their use. The existence of a legal power or liberty is one thing; the justice or advisability of exercising this power or liberty is another matter entirely.

To be sure, there isn’t, alas, a convention against using the notwithstanding clause in the way there is one against using the disallowance power. But that’s no justification for using it either. At most, it means that a legislature is entitled to consider using the notwithstanding clause on a case-by-case basis. But that’s dangerous and unwise, because legislatures do not think well about how to exercise this power.

The outraged reactions to Cycle Toronto, which treat it as a self-evidently wrong instance of judicial activism help explain why: people, and that includes ministers and legislators, are quick to condemn that which does not make intuitive sense to them, without analyzing it. To be clear, I do not mean that anyone who’s taken the time to think about it must agree that the case was correctly decided. But I do think that such a person would see that it is not about a putative right to bike lanes or a judicial takeover of all planning decisions or something of that sort. Maybe Justice Schabas got things wrong, but the downside of this decision, assuming it is even upheld on appeal, strikes me as pretty limited.

So the reactions to it do nothing to change my view that support for the notwithstanding clause is nothing more than opposition to the Charter as a whole. The people who demand that it be used whenever they encounter a judicial decision they do not like simply do not want to see the decisions of governments put to the test before a forum where, as I discussed in my last post, culture war rhetoric — whether in favour of a maximalist conception of trans rights or, as here, against bike lanes — holds no sway. I think the “political constitutionalist” view that rights issues are not suited to judicial resolution is an intellectually respectable one — but that is on the condition that it is advanced transparently. But this transparency is missing in Canada these days.

I will say, though, that I find the political constitutionalist argument singularly unpersuasive in the circumstances that have given rise to Toronto Cycle. Political constitutionalists say, instead of litigating everything, why don’t you win an election or persuade the people who have? Well, that’s exactly what the pro-bike lane people did in Toronto. It wasn’t the courts who built all those bike lanes: the democratically accountable city authorities did, presumably because their constituents wanted that. In comes a legislature that is essentially a stranger to the matter, most of which is elected by people who do not live anywhere near these bike lanes and won’t ever drive on the affected streets, acting at the behest of a premier with a longstanding grudge against the city. If you think that that is what we need to protect and cherish in the name of democracy, then I think you understand democracy all wrong.

The Superior Court’s decision in Cycle Toronto is counterintuitive, but it is actually right. It is sensitive to concerns about the ratcheting of constitutional protections to matters that should remain within the discretion of policymakers, and even, at least to a degree, to the challenges of deciding cases on the basis of potentially flawed empirical evidence. It certainly justifies neither the vituperative opposition it has provoked nor the calls for the notwithstanding clause to be used to undo it. The people who have indulged in such calls should take off their clown noses and be honest: it is the Charter itself they want to undo, and not in the name of democracy, but simply of a vindictive, arbitrary government’s ability to indulge its fancies.

Leave a comment